America finds itself sitting on the fence in the debate over the use force in not one but two conflicts: Iraq and eastern Ukraine. Washington is simultaneously playing diplomatic go-between in a third conflict in Gaza. And Syria continues to burn uncontrollably. President Obama has spent much of his presidency trying to extract the U.S. from a pair of Middle Eastern conflicts in order to pivot to the East, but finds himself in Michael Corleones position: Just when we thought we were out of the region, we get pulled back in.

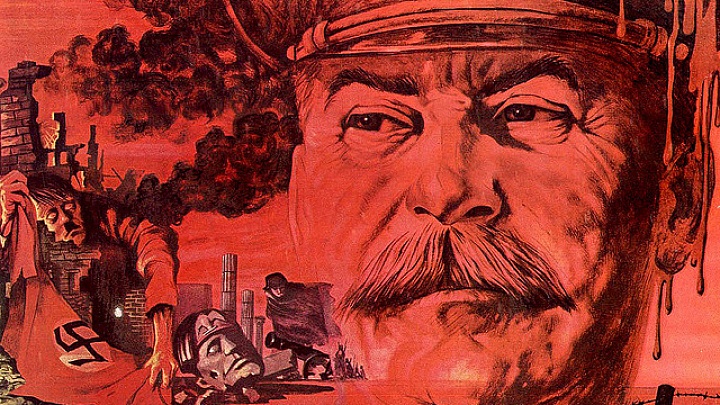

Russia’s own Godfather, Vladimir Putin, decided to undertake a Stalin-esque annexation of the Crimea and continues further intrigue in eastern Ukraine, including the senseless downing of a civilian airliner by Russia-controlled rebels. Like clockwork, war then returns to Gaza. All this and America has not even begun to turn its attention toward what may be its greatest future strategic opponent—China. This provides clear evidence that the world is still as dangerous a place as it always was. So how should America decide to use force?

Every conflict America has fought in the post-WWII era has carried with it the potential to expand into a much wider conflict—WWIII even. Even seemingly small crises such as the Cuban Missile Crisis or the fall of the Berlin Wall carried the specter of a much wider battle if things had gone differently. America did not go all in in Korea because it risked all-out war with China and the Soviet Union. During Vietnam, a larger commitment beyond the borders of Vietnam risked the same and thus limited U.S. military activity to only temporary incursions into Laos and Cambodia.

If America decides to use force, it should do so with clear, pre-defined objectives with the commitment to see them through to victory. If it cannot muster this, it should not use force at all. But the fact that America was wrong in Iraq in 2003 should not stand in the wayif the use of force is called for in 2014.

This did not change after the Cold War ended. Colin Powell urged George HW Bush not to go all the way to Baghdad because America would then own the problem of how to rebuild a country. Bushs son did not follow bin Laden, al Qaeda, and the Taliban into Pakistan because it did not want wider war in the Middle East. This despite the stated goal of the campaign being to apprehend or destroy those responsible for the 9/11 attacks and strong evidence Pakistan was playing for both sides.

America often avoids direct military confrontation, and even when it has gone to war in the post-WWII era, it has fought mostly limited or small wars—UN police actions, counterinsurgencies, or humanitarian actions accompanied by small skirmishes. In reality, most of these conflicts were proxy wars with the Soviet Union, China, or even Iran. These were wars in which the two main combatants never actually squared off.

For some policymakers, military commanders and commentators, the 2003 Iraq War laid bare that fact that Americans have a hair trigger for conflict; that their threshold for the use of force is much lower than prudence should dictate; and that their ideological commitment to certain ideas and a certain worldview is stronger than their understanding of reason, facts, and objectivity. Many neo-conservative members of the younger Bush administration fit this bill, with Dick Cheney and John Bolton providing caricatured examples. As another, over the past 10 years, John McCain, despite being often at odds with Bush, has recommended the forcible regime change in at least six countries and to take military action in half-a-dozen more. His credibility should be deeply questioned.

However, on the other side of the spectrum are those who believe force is never the answer, or that the use of force outside of a UN mandate is illegal, or that the U.S. should use military force only when America or its interests are directly threatened. Some have added the caveat that the threat to America must be existential to justify the use of force. These Liberals are as committed to their ideology as neo-conservatives, and their credibility should be questioned as well.

Many Liberals—and others—point to the Iraq War as an unnecessary war of choice that was begun under false, fabricated pretenses and has cost us far more in blood and treasure than it was worth. They are correct. Iraq today it is perhaps as threatening or dangerous a place to America as it was under Saddam.

A New Kind of Powell Doctrine?

The hesitancy exhibited by the Obama administration to commit to the use of force is not wrong. Before America goes to war it should always decide if it is willing to go the distance. There are times when a limited, focused campaign can achieve results—see Bosnia, Kosovo, and Libya. But this is the exception and not the rule. Lack of a clear mission with defined goals and commitment to full victory can lead to quagmire and mission creep, as in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. The current administration’s hesitancy to become involved on the ground in Syria and now Iraq (again) and Ukraine seems to come from an understanding of this problem. One should not sleepwalk into wars, as WWI teaches us, or try to fight them on the cheap, as we did early on in Afghanistan.

However, not every war is Iraq. Not every conflict is one which can be blamed on political intrigue by America at some point in decades past coming back to haunt us. Not every confrontation can be one that the U.S. is instigating for economic gain or to secure resources such as oil. Not every war is part of a racist program of Orientalism to oppress the East. Not every fight is part of a capitalist struggle to repress the working classes. Not all evidence of grave crimes being committed—such as nerve agent attacks against civilians or the downing of civilian airliners—should be brushed aside as we wait for indisputable, ‘smoking gun’ evidence that points to the perpetrator. That evidence will never come—international bodies such as the UN and OPCW [Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons] never point fingers in their conclusions.

As the 20th century has turned into the 21st, moral justifications for going to war have become unclear, politicized, and suspect. There has been revived interest in just war theory, but war is never just. Even under the most clear of circumstances and for the most altruistic of reasons, innocent people die. As sure as there has always been and will always be war, innocent infants, children, women, old people, and even dogs will be killed in war. Try to explain to a man whose wife has just been killed that it was just. War (contrary to this magazines mission statement and words of its namesake), is not just; war is war.

Yet, despite this, there has never been as much care taken in the military operations of Western states for avoiding unnecessary civilian casualties in combat as there is today. Civilians are a consideration in every engagement. We have gone from indiscriminate day-and-night bombing raids on European cities during WWII to using intelligence-driven surgical strikes on individual targets. Though controversial, drone strikes are one of a few ways America acts against opponents who don’t have a state or wear a uniform that does not require boots on the ground or put troops’ lives at risk. It is a prudent use of force.

The other alternative is to do nothing. Doing something—ground combat, air interventions, drone strikes—is just as unpalatable as doing nothing. But doing nothing allows opponents and extremists to control ever-wider swathes of territory in places like Syria, Iraq and Ukraine. The U.S. obeys international laws and conventions, and the aggressors such as Assad and Putin and militant non-state actors such as al-Qaeda and ISIS do not—to the terror of the innocent people who live along their paths. Doing nothing is also a choice on America’s part.

Will there ever come a time again when it is clear America must act? A war with as strong a moral imperative as WWII or as clearly diabolical an enemy as National Socialism is not likely to happen again anytime soon. It is right to always be skeptical of the use of military force. War is an ugly thing for everyone involved and it is always right to question it. However, there does come a time to use force as the ‘last argument of kings’.

Hybrid Uses of Force

The ambiguous nature of warfare of the 21st century is not by mistake, but by design. The U.S. military has come to dominate all facets of the battlefield more than any other military in world history. Though states such as Russia, Iran, Saddam’s Iraq, and North Korea have rattled their sabers against the United States, they still toe the line in the open. Instead, those who wish to challenge the U.S. do so today through a concept characterized as hybrid warfare, which combines proxy war, espionage, subversion, terrorism, and information warfare into a conflict in which the real enemy or aggressor is obscured or buffered from it. The current situation in Ukraine is a perfect specimen. Putin seems to be taking a page from Nikita Khrushchev’s playbook and constantly testing the surface tension of the situation—seeing how far he can fill the cup without it actually overflowing.

By convention, any military action would require a UN mandate. But what if those who are perpetrating or supporting the very acts of aggression in question (in Syria and Ukraine) sit on the UN Security Council? The UN is subject to the same influences and politics every large governmental organization is and ceding to the UN the decision to authorize the American use of force in all circumstances is to cede the ability to act to an organization that is just as subject to international politics as America’s government is subject to domestic politics.

Those Liberals and Conservatives who are weary of the domestic politics and motives of America’s national government should be just as weary of the international politics and motives of the United Nations. It is no more fair or impartial an organization than the U.S. Congress or executive branch. As the conflicts in Syria and Ukraine show, waiting favors the aggressors on the ground. They only see cease-fires and negotiations as a strategic pause in their campaign to rest and gather forces, a view many partisans on both sides of the Israel-Palestine conflict also share.

Forget Shock and Awe

The judgment of many Americans suffers from Iraq Syndrome, a disease characterized by doubts that the use of force can ever be justified except in extremely clear circumstances, a disorder that is a weaker version of the collective guilt felt by Germans and Japanese following their war crimes of WWII. The 2003 Iraq War never should have happened. Thousands of American troops and tens of thousands of Iraqis have paid the price and the real perpetrators—the Bush administration—will never answer for it. However, the crimes America’s leaders have committed should never hold future leaders back from the good America can do. The decision to use force is never an easy one and should never become too easy. But there does come a time for it.

Related to this problem is the thinking of those in policy circles who still continue to hope against hope that Francis Fukuyama’s End of History thesis is true in the face of overwhelming evidence it is not. Though the U.S. came out of the Cold War victorious, the peace promised has not materialized. This was apparent almost immediately. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. The Gulf War, Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, and finally 9/11 followed in short order. Perhaps the average American academic or bureaucrat can be excused for believing the world is less dangerous. The U.S. has been simultaneously fighting two grinding counterinsurgency wars in far-away lands half a world away over the last decade without any ill effects being felt on the home-front. Few countries have the luxury of being able to project global military force while the people back home continue life as normal. For most Americans today, war only happens on TV.

Strangely, those members of the George W. Bush administration responsible for this Iraq Syndrome in the American psyche are now being invited to reappear on television to give advice on how to respond to the ISIS invasion of Iraq, like an abusive husband convincing his wife it was her fault and she should have heeded his warnings. Those who argue that ISISs reemergence in Iraq is a result of the U.S. not staying the course should also acknowledge that none of this would have happened if the U.S. had not invaded Iraq in the first place. They are the last people America should listen to on the use of force.

So when should the U.S. use military force? There is no sure checklist or decision matrix to consult in order to justify the use of force in all circumstances. Whether force should be used in answer to events in eastern Ukraine or Iraq is a difficult one. What is clear is that if America decides to use force, it should do so with clear, pre-defined objectives with the commitment to see them through to victory. If it cannot muster this, it should not use force at all. But the fact that America was wrong in Iraq in 2003 should not stand in the way of the objective consideration of the question if the use of force is called for in 2014. America needs to shake its Iraq Syndrome, forget the End of History, and move beyond its post-9/11 past, especially if it ever hopes to tackle its larger strategic concerns of the future and pivot to the East.

Chris Miller is a U.S. Army veteran and Purple Heart recipient following two tours in Baghdad, Iraq and has worked as a military contractor in the Middle East. His work currently focuses on strategic studies. His interests are CBRN, military and veterans issues, the Cold War, and international security affairs.

[Photo of ISIS militants courtesy of Flickr Commons.]