Throughout the Cold War, China remained secondary to the Soviet Union in American strategy and thinking. Ironically, the Asia-Pacific region was where the Cold War got the hottest in places like Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia and was home to a relatively minor nuclear power, China, which often proved the most antagonistic to American interests. Now, after the Soviet Union devolved into a weakened Russian Republic, the rise of Chinese power has caused the United States to “rebalance” to the Asia Pacific region and toward China in particular. Ignored the first time around, understanding and responding to Chinese nuclear strategy are vital aspects of the “Asia pivot.”

It would be comforting to simply assume that the nuclear policies successful in deterring a major war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union will apply again to China. While communism provides a façade of similarity, advancing technologies and cultural differences demand that this assumption be re-examined and challenged. Successful deterrence is a communicative art that, in the nuclear arena especially, defies simplistic solutions. America must take an approach based upon a new, specific examination of Chinese policy.

Nuclear Deterrence

Nuclear deterrence strategy is a difficult subject, and understanding and responding to Chinese strategy today requires at least a basic understanding of its general principles. The “first strike strategy”, whose effectiveness is measured by how much damage an enemy can do to their target after the first strike, requires accurate missiles, an active missile defense to destroy what is missed, and passive “civil defense” as a final layer to protect civilians against those missiles that “leak” through. “Second strike” strategies focus on nullifying the three pieces of first strike to such a degree that the damage that can be inflicted after the enemy’s first strike is so horrific as to render a first strike unthinkable.

Required for both strategies is a rock solid command and control (C2) system that ensures no accidental or unauthorized launches, but remains survivable after any attack and able to wield the surviving retaliatory capability. First strike remains an operationally offensive capability to meet a strategic defensive policy; namely status quo maintenance. Second strike is an insurance policy for an aggressive nation to ensure their conventional conquests are unchallenged by a nuclear sword of Damocles. Many have argued convincingly that the lack of effective first strike capability by either the Soviet Union or the United States during the cold war, the “MAD” (Mutual Assured Destruction) equilibrium is what kept the Cold War from going hot and led to the relative stability of the post-WWII global scene.

Modern Chinese Strategy

Chinese strategy, while borrowing heavily from Marxist-Leninism on the surface, remains grounded in Sun Tzu and Mao Tze Tung. The terminology used in modern Chinese strategy will be instantly recognized by any Sovietologist. A key difference being that the core of Soviet thought was the inevitability of both an existential conflict between Capitalism and Marxism and the inevitability of the ultimate global triumph of Marxist ideology. This led to a patient policy that did not seek to challenge the western interests in the absence of certain success. China, however, currently retains a more nationalistic point of view. Domestic stability and expansion of near territorial claims in the name of China, not global communism, is their stated priority. Moreover, China’s Communist Party now apparently perceives China as the victim of “hegemons” seeking to establish dominion over China and her interests. The inevitable triumph of China is not an assumption, but rather a goal to be actively pursued. So while patient in their own way, Chinese patience may not be same model the United States faced from the Soviets during the Cold War.

Chinese nuclear policy reflects both similarities with and differences from the Soviet and American models. China has a no first use policy which, if true, requires it focus on a second strike, counter-value nuclear strategy. China’s claimed capability reflects this strategy. With less than 50 ICBMs capable of reaching the United States and topped with large, single warheads, China’s inventory is best suited for targeting large cities. China does not have a significant force of inter-continental bombers and its submarine fleet remains small and inexperienced. China’s vastly improved and demonstrated space capabilities, however, indicate that they are capable of rapid advancement of their nuclear delivery technology. Consequently its current status could be quickly and dramatically improved.

Confusing the issue is that China deliberately obfuscates its nuclear capabilities. Western deterrence theory has been built upon a foundation of improved openness in order to facilitate arms reductions with both the Soviet Union and Russia. America’s nuclear delivery TRIAD capability of ICBMs, SLBMs and bombers remains open and unclassified. The same cannot be said of China’s capabilities. Their actual numbers of ICBMs and warheads is unknown. While orthodox analysis estimates low numbers, some estimates have the Chinese capability an order of magnitude greater. China eschews any strategic arms limitation talks which would necessitate an ability to verify their capability. Why China chooses to do so could be either from a fear of displaying weakness or desire to keep a stronger capability secret.

The deception inherent in both Chinese strategy and nuclear policy also can extend to its oft stated, “No first use policy.” Strategic arms have often been equated to “nuclear weapons.” Both American and Soviet/Russian war planners flirted with tactical nuclear weapons. But the destruction inherent in even these “low yield” weapons is so great and the public perception of any nuclear use being repugnant that they remain in the hands of the highest policy makers and thus remain strategic by definition. Rather than making nuclear weapons tactical, both China and the United States have started to see high-technology, conventional weapons as strategic. This blending of the conventional and nuclear at the strategic level brings nuance to the Chinese declaration of “no first use.” It could be that no first use of strategic weapons means a high tech conventional attack on a strategic target would be causus belli to use other strategic weapons. Moreover, public statements by Chinese officials have openly brought into doubt the “no first use” when concerned with areas of conflict such as Taiwan.

Chinese nuclear strategy and capabilities are, at best, a series of assumptions that leave open room for doubt for both hawks and doves. The transparency that many believe brought stability to the cold war remains an elusive goal when dealing with Chinese nuclear deterrence.

Nuclear Deterrence & Modern China

Hans Morgenthau reminds us we must view these principles from a current Chinese perspective. Despite our primary focus on the Soviet Union, China was keenly aware that any nuclear capability effective against the Soviet Union would be overwhelming if directed against China. Furthermore, American capabilities were often explicitly directed against China. The U.S. nuclear arsenal was seen as a check on Soviet aggression in Western Europe and they were also used during the Korean conflict, not against North Korean troops, but as a lever against China. President Eisenhower and CIA Director Allen Dulles attributed the threat to use nuclear weapons as the primary tool to break the stalemate with China in Korea. China was ultimately forced to accept not only the status quo ante bellum, but also a humiliating abandonment of their policy of forced repatriation for communist prisoners. From 1954-1958, China was again subjected to the threat of nuclear retaliation several times.

The purpose of the highly-contentious area defense “Sentinel” system was explicitly stated by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to counter the Chinese nuclear threat, not the Soviet one. While this public proclamation could be seen as simply verbally assuaging Soviet and domestic concerns of destabilizing the nuclear balance it can also be seen prima facie as an undue U.S. fear of Chinese nuclear intentions. Several times during the Cold War, deterrence implicitly designed against Soviet capabilities was publicly focused on China.

Today, both the Russian and American nuclear inventories are greatly reduced. On the U.S. side, the first strike ICBM force has been slashed to only 450 warheads. While incapable of severely reducing the Soviet land based retaliatory capabilities, it provides an intimidating threat against the most likely Chinese capability. Several U.S. warheads could be targeted against each Chinese ICBM. The Chinese are developing mobile ICBMs utilizing a tunnel system to mitigate this threat, but the Chinese can never be sure how well U.S. intelligence has penetrated the secrets of Sino nuclear deterrence.

The improving GMD (Ground-based Mid-Course Defense) system is unquestionably a cause for concern for China. John Holum, former U.S. State Department chief of arms control, stated, “The Chinese see missile defense as part of a grand design aimed at China.” Only a decade ago, the five interceptors were a minimal threat to China’s deterrence. But now the Obama administration, far from a hawk on missile defense, has promised to increase the current inventory to 44, nearly matching China’s entire ICBM fleet. That is an order of magnitude larger inventory in only ten years. Publicly, the U.S. says the deterrence is designed against emerging threats such as North Korea and Iran. But publicly the U.S. also said Sentinel was directed against China. Has the public deception now flipped? It is hard to justify 44 interceptors to counter the current or even future estimated North Korean nuclear capabilities. Both their warheads and their missiles are of questionable quantity and quality. The current GMD system is designed to counter warheads specifically, not missiles. The single warhead capability which China supposedly possesses is more easily countered by GMD than Multiple, Independently-Targeted Re-entry Vehicles (MIRVs) previously used best online casino by the United States and currently used by Russia. The West Coast based system in California and Alaska is well-situated to provide defenses against a North Korean launch. But the geographical proximity of China to North Korea cannot be ignored by either party. We can deny GMD is focused on China in all honesty. But China cannot ignore the simple fact that, accidentally or otherwise, GMD poses a direct threat to their second strike deterrence.

The terrorist attacks of the post-Cold War era have given impetus to the development of greatly improved domestic response capabilities. Their title is no longer civil defense, which described their purpose, but rather now describes the threats they defend against: Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and Explosive (CBRNE). Since 1996, the United States has invested heavily in the US military and civilian first responder CBRNE defensive capability. Every major city’s fire department is trained in radiological response. The US DoD has likewise invested greatly in National Guard CBRNE capabilities. Each state and territory has at least one full time response team and each of the ten Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) regions have a robust National Guard unit dedicated to search and rescue, medical support and radiological decontamination. While no one can say these teams were designed as part of a Herman Kahn-ian first strike plan, the fact is these teams do support that 50 year old concept. As pure coincidence, FEMA was created by combining the various civil defense organizations created in response to Kahn’s ideas.

You cannot talk about American strategy against China without talking about Air Sea Battle (ASB), the conventional operational concept developed partially, if not mostly, to counter Chinese expansionism. The details of ASB change as required, but the original, and most bellicose, description came from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Analysis (CSBA) which describes utilizing advanced conventional strike capabilities to target not only China’s conventional military, but also its command and control. The new TRIAD may now be applied to target the heart of all nuclear deterrence; its trigger. So while ASB may specifically decline a nuclear integration, if successful in its implied operational objective of isolating the political control of its enemies’ military, it would effectively and surgically neuter its nuclear deterrence as well. Remember, too, China sees conventional high tech warfare as a part of modern nuclear combat.

China may continue to openly state a “no first use” policy, but expect Chinese opaqueness to render the truth of these statements questionable.

Here we have four separate elements of the U.S. defense establishment seemingly developed independently combining to counter China’s current estimated nuclear deterrence. If the heart of stability is found in the sanctity of both parties’ second strike force, then we are rapidly approaching an increasingly unstable future vis a vis China. From this assumption, predictive analysis is possible.

How Will China Respond?

The sine quo non of super power sovereignty is effective nuclear deterrence. China must respond in the face of openly stated American capabilities and operational concepts. The U.S. 44-GMD-interceptor capability can expect to be countered through an increased warhead count, either through more ICBMs or the development of a MIRV capability. While a Chinese nuclear submarine force is being developed, U.S. Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) has an 80 year history of success. It would be questionable for China to invest its deterrence capability in submarines so early in its own history of submarine warfare. To increase survivability, China is already investing in endo-atmospheric hypersoniccapabilities for its warheads. This could conceivably nullify GMD’s abilities, though its technological viability is still questionable.

China may continue to openly state a “no first use” policy, but expect Chinese opaqueness to render the truth of these statements questionable. American policymakers must be sure to be as inclusive as possible in determining exactly what no first use means with every conceivable nuance taken into account. Finally, China may utilize the brute force mechanism of simply building an unassailably large arsenal of missiles. A new arms race may be the only technologically viable mechanism available for China to maintain a reliable second strike. And as long as ASB maintains its insistence upon striking the Chinese mainland, a more decentralized nuclear command and control mechanism is a logical counter. The combination of larger nuclear forces and an increasingly decentralized command structure might be the price China must pay.

Two of these elements (ASB and the 44 interceptor fleet) remain years away from operational status. China currently has a window where their current nuclear deterrence remains relatively strong. China may take this near-term opportunity and accelerate its forceful advancement of territorial claims in the Asia-Pacific region. Rather than improve its nuclear deterrence, China may simply move quickly to establish a new status quo in a conventional manner before the US has its more robust first strike capability established. China’s recent actions in the Spratleys and Senkaku islands could reflect this strategy. American current and planned actions should elicit a Chinese response. Whether this will be near term conventional aggressiveness or a long term buildup of their nuclear forces (or both) is unknown.

What Can America Do?

Should the United States adjust its policies to assuage Chinese concerns? One has to ask which parts of this four-headed hydra (civil defense, ASB, missile defense and ICBMs) the United States would be willing to abandon. Our civil defense capabilities are clearly required in the wake of successful and attempted terrorist attacks both in the United States and abroad. Its linkage to our nuclear posture is a vestige of a generation past. It is by far the weakest aspect of any first strike capability and one that most likely enjoys the highest level of public support. Our ICBM force is an established part of America’s TRIAD of nuclear deterrence. Anything short of complete removal of this leg will do little to change the balance of deterrence and is a political decision that appears unreasonable in the near future. And it doesn’t eliminate the use of submarine launched missiles in a first strike role.

GMD is likewise a political winner with admittedly vocal detractors. The bedrock of all deterrence is rationality amongst all players. To eliminate GMD would require an assumption of rationality from all current and would be nuclear powers. Iran and North Korea may behave rationally, but are their underlying grand strategies equally rational? Henry Kissinger identified that communicating suicidal tendencies has a rational role for weaker powers. U.S. policymakers would be betting the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans on the rationality of the current and any future North Korean dictator. The number of interceptors, rather than the program itself, is the most likely mechanism to adjust China’s possibly negative perspective. A shift of funds from operational interceptors to more robust testing could be reassuring for both the United States and China.

Finally, ASB must be reappraised from a nuclear deterrence perspective. A fair assumption on the part of China is that, should the U.S. utilize the thousands of strike fighters and bombers being justified, in part, to support the ASB concept, their command and control elements will be targeted to isolate them from their deployed forces or destroyed completely. That these C2 elements might also control China’s nuclear deterrence cannot be ignored. Even if the United States adopts a clearly limited strategy, this does not mean that the Chinese fear of India or Russia taking advantage of their weakness is removed. We must see the targeting of high level C2 elements in China as a nuclear level provocation and treat it as such.

Thus far, China has eschewed meaningful participation in strategic arms limitation talks. Two of its three largest threats, Russia and the United States, are providing a free ride for China as current strategic arms treaties demand openness and verification of nuclear capabilities. China knows what each has with nothing given up on their part.

In the face of a growing American capability, this will not change. Should the U.S. wish to entice the Chinese to a more open nuclear posture, all aspects of our nuclear deterrence, even those which we do not consider a nuclear threat to China, must be part of the discussion. Whether we say it or believe it, GMD and ASB, as well as civil defense and, of course, our nuclear TRIAD, all pose legitimate threats to Chinese nuclear deterrence. As Sun Tzu reminds us, “If you besiege an army, you must leave an outlet.” We must likewise be aware of the pressure we exert on China’s nuclear deterrence and leave an outlet if we wish to duplicate the successful deterrence we enjoyed in the Cold War in a 21st century multi-polar nuclear environment.

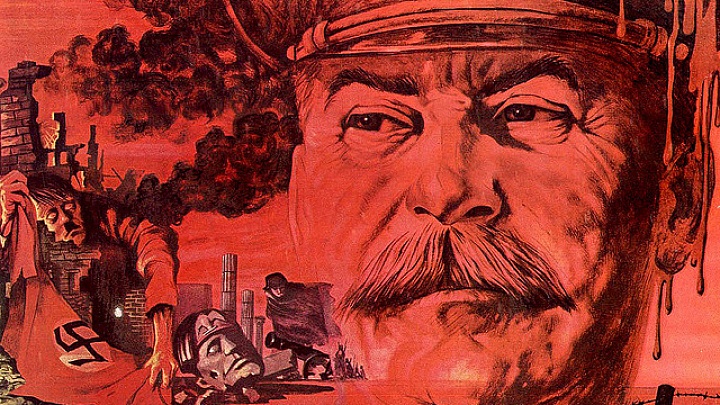

[Photo: Flickr CC: Chinh Dang Vu]

China multiplies the strength of its nuclear arsenal visa vie the United States and Russia by keeping it opaque.

Rather than investing huge sums into nuclear weapon overkill as Russia and America have done they have selected a more obscure and in fact clever strategy that inhibits definition but counter-strategy. Confusion to your enemies!

This approach makes sense in China’s particular case. It reduces cost and vulnerability of large nuclear systems while at the same time performing the essential strategic function of deterrence.

If the United States does not like that Chinese approach and wishes for more openness that confirms to the Chinese that they have achieved the right strategic formulation.

It doesn’t appear the article is arguing the current ineffectiveness of the Chinese strategy. The point is that China nuclear strategy and Soviet/Russian nuclear strategy are different, but the US doesn’t appear to be adjusting its own deterrence strategy accordingly.

No doubt the US has an 80 year old submarine history and is top of the pack in this field.

Bear in mind nothing is permanent in this world.No doubt the US nw greatly outnumber the PLA by a a mammoth margin.

The PLA will work to ensure a sufficient number of nw will get through the targets in spite of US Sdefences.What this number is we don’t know but at least ten to 50 of the biggest population scentres will be hit.Even if the Pentagon can destroys China’s nm,this threat will be sufficient enough

to convince the WH,there wont be a 100 % success.

Btw the PLA will go all out to ensure China wont be anked and defenceless like in the past.

China must have five thousand nm . Then and only then will the US

treat it with respect. All the air sea concept will be irrelevant once China has enough

nm to get through US missile defences and make sure the WH doesn’t even think

about starting a nw.

Btw,shd the US want 99.9% security,China will make absolutely sure the damage to US

assets will be unthinkable.And don’t give the bs China’s modernisation is a threat to

the international community,read US.If you aint athreat,China wont be one either.

A little history will explain China’s nuclear deterrence policy.During the Korea war and Taiwan crisis 1954 and 58 as well as 1996,the US had threatened China with nuclear attack.I believe during the cold war,according to declassified reports, the siop had singled out China as one of the countries to be hit with nw.Mao had once said if China didn’t want want to be bullied the PLA must have nw.

China will use nw only in self defence. For the info of Americans,the pentagon wanted to hit /destroy Cuba with nw . However they could not be 100%sure a Soviet Union missile will not hit the conus.

EEven with the missile shiedl,I am sure the PLA will increase their stockpile of nw to make 100% sure the US wont be immune from na shd the Pentagon initiate an strike.